Introduction

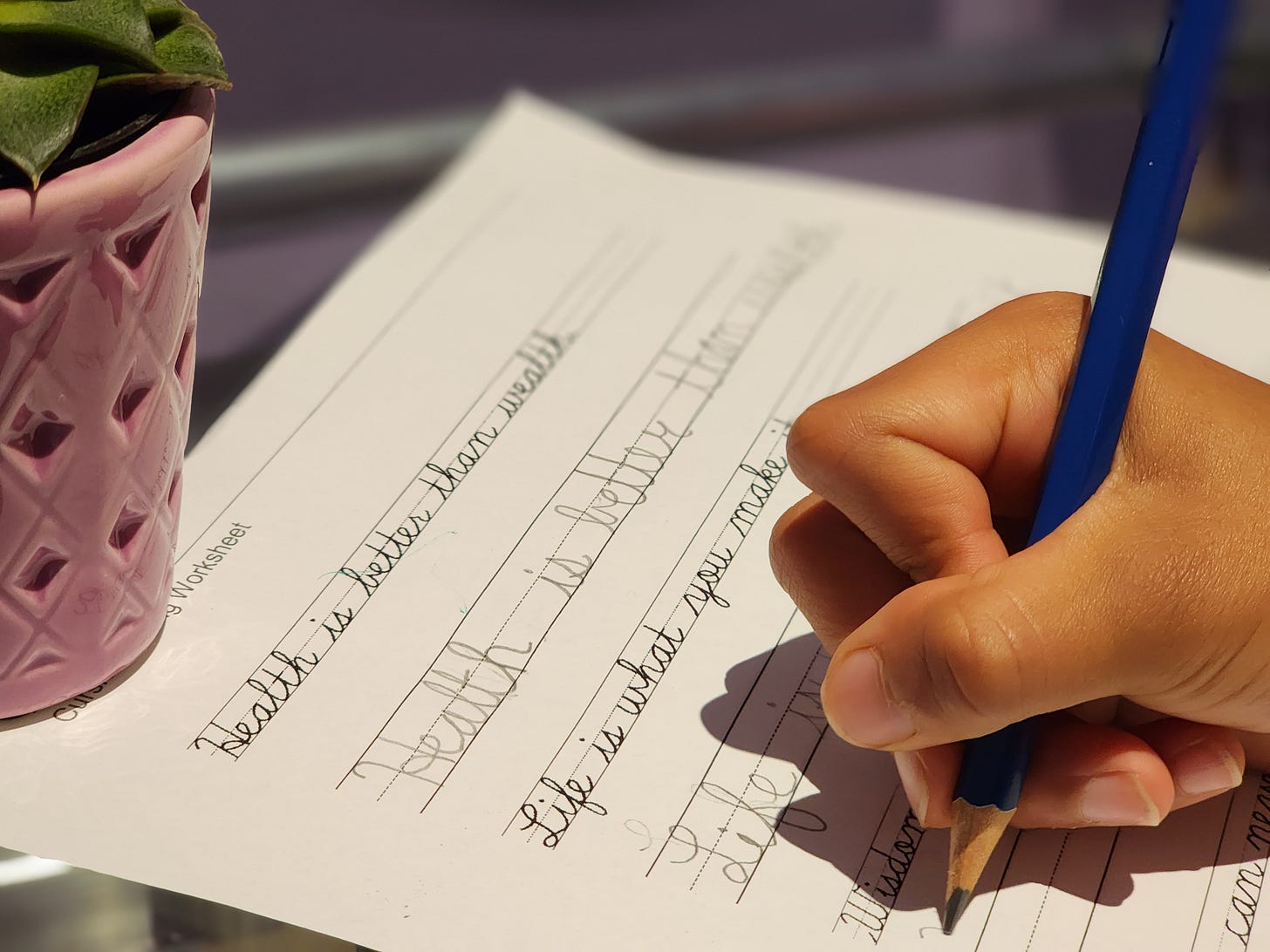

The Ontario government recently announced that cursive writing, which was dropped from the elementary curriculum in 2006, will be made mandatory again in the upcoming school year. This development has sparked tremendous interest and debate. Some people have voiced disapproval, arguing that cursive is no longer a useful skill in a highly digital world. Others have applauded the change, insisting that cursive writing is beneficial for young writers, offering them another means of expression.

The issues surrounding school handwriting policies tend to be complex and multifaceted. Handwriting is taught in different ways around the world. The word “handwriting” refers to any kind of writing by hand, including printing and cursive styles. In Ontario, and in most North American schools, children are initially taught printing (also called “ball-and-stick” or “manuscript” handwriting), at age 5 or 6. Instruction in cursive writing, if it is taught at all, occurs between the third and fifth grade. In Europe, cursive handwriting or D'Nealian handwriting is often taught first. D'Nealian handwriting is a hybrid script that combines elements of printing and cursive writing.

In the 2000s and 2010s, many educational institutions across North America began to place greater emphasis on digital literacy and other skills that were deemed more relevant to the modern world. This shift led to a decrease in the amount of time dedicated to cursive writing instruction. Some educational jurisdictions, like Ontario, decided to remove cursive writing from the mandatory curriculum. Consequently, many were surprised to learn that Ontario was going to reverse course and reinstate cursive instruction. Minister of Education, Stephen Lecce, offered the following explanation:

“The research has been very clear that cursive writing is a critical life skill in helping young people to express more substantively, to think more critically, and ultimately, to express more authentically” [Minister of Education Stephen Lecce as quoted by Allison Jones, The Canadian Press, June 22, 2023]

We were fascinated by Minister Lecce’s comments about educational research. Does cursive writing really foster critical thinking? Does it help young people express themselves more substantively and authentically? Has research shown that cursive writing is superior to printing in these respects?

We decided to review the research literature for evidence of Minister Lecce’s claims. Here is what we found:

For young children, handwriting (either printing or cursive) is better than typing on a computer for improving spelling accuracy, letter recognition, memory and recall.

Handwriting is an important part of language development. The physical activity of carefully shaping each letter fosters a deeper familiarity with words. Comparative studies reveal that handwriting is superior to keyboarding in terms of fostering letter recognition, promoting the recall of words, and improving spelling accuracy (Cunningham & Stanovich, 1990; Longcamp et al., 2008; Longcamp et al., 2006; Smoker et al., 2009, Wiley & Rapp, 2021). This collective body of research suggests that handwriting (which can take the form of cursive or printing) is a better support for early literacy development than typing on a computer.

There is no evidence that cursive writing offers greater cognitive benefits for students than printing.

Cursive writing is a manually smoother process than printing. The pen remains on the page longer and there are fewer stops and starts. This might lead people to wonder if the more fluid and forward-moving nature of cursive writing better supports the flow of ideas, fosters creativity, or promotes critical thinking.

Our review of the literature failed to find any evidence of advantages for cursive writing. We think it is unlikely that cursive offers more cognitive benefits than printing, or vice versa.

There is no evidence that printing imposes a higher (or lower) cognitive load on working memory.

We found no evidence that printing and cursive affect cognitive load differently. Initially, handwriting (of any sort) demands focus and concentration. With practice, students develop fluency and automaticity. Once writing becomes automatic and effortless, working memory is freed up, allowing the learner to better focus on higher order aspects of composition. This works the same way for both forms of handwriting.

Comparative studies of writing speed have failed to find significant differences.

Comparative studies of printing and cursive handwriting date back to the 1920’s. Many of these studies focused on speed and legibility. In most cases, speed differences are minimal or non-existent (e.g., Washburne & Mabel, 1937; Jackson, 1971; Hildreth, 1944). Faster writers sometimes employ a hybrid of printed and cursive text (Gates & Brown, 1929; Graham, Weintraub & Berninger, 1998). In terms of legibility, printing tends to be more legible than cursive (Gates & Brown, 1929).

How do these findings inform the current debate in Ontario?

Our review of the research suggests that handwriting (printing or cursive) is important in the early years, and a good deal of time needs to be dedicated to it. It would be a mistake to replace it with keyboarding.

We found no evidence that cursive writing is educationally more beneficial than printing. Hence, we are skeptical of the Minister’s claims that the decision to reinstate cursive in Ontario is backed by research.

Summary:

We felt there were a number of useful take-aways from our review of the literature:

In the elementary grades, handwriting of any kind (either printing or cursive) has been shown to be superior to keyboarding (i.e., keyboard-entered text) in terms of fostering letter recognition, spelling, and word recall among developing readers.

A review of the literature found no evidence that cursive writing is better for students than printing. There are no consistently documented speed advantages. There are no reported differences in the quality or creativity of students’ writing. There is also no evidence that cursive writing is more supportive of critical thinking or other higher-order cognitive processes.

The claims made by the Minister of Education are not backed by research.

Whether one teaches printing, cursive, or both, the goal should be to help students develop fluency and automaticity. Handwriting needs to be practiced until it is as automatic and effortless as possible. This allows working memory resources to be fully applied to higher order aspects of composition.

The purpose of our literature review was to examine the Minister’s claims and bring clarity and transparency to the public debate. Given the complexity of educational research, it is often necessary to carefully check the claims that people make. Experimental studies can be complicated and nuanced, and they are highly vulnerable to oversimplification or misinterpretation.

In the current case, we were unable to find academic studies that substantiated the research claims made by Minister Lecce. Student handwriting is indeed a highly beneficial activity. However, the literature offers no evidence that cursive writing is somehow special in terms of fostering critical thinking or helping children express themselves more authentically.

None of this is to suggest that the government’s policy is misguided. There are indeed reasonable arguments for bringing back cursive writing: it equips students with the ability to read and write cursive text, offers another mode of communication, and improves students’ fine motor control. Our concern is not so much with the policy itself, but rather with the misrepresentation of research findings that could potentially mislead the public. To maintain a trustworthy and informed public discourse, researchers and teachers need to continually examine questionable claims and insist upon accurate and fair depictions of the research literature.

If you’ve come across a study that informs the debate about cursive writing, we’d love to hear from you! Please share it with us. We’re particularly interested in studies that compare cursive to print writing.

References

Cunningham, A.E., & Stanovich, K.E. (1990). Early spelling acquisition: writing beats the computer. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82, 159-162.

Gates, A., & Brown, H. (1929). Experimental comparisons of print-script and cursive writing, The Journal of Educational Research, 20(1), 1-14.

Graham, S., Weintraub, N., & Berninger, V. (1998) The relationship between handwriting style and speed and legibility, The Journal of Educational Research, 91(5), 290-297

Hildreth, G. H. (1944). Should Manuscript Writing Be Continued in the Upper Grades? Elementary School Journal, 45(2), 85-93.

Jackson, A. (1971). A comparison of speed and legibility of manuscript and cursive handwriting of intermediate grade pupils. Ed.D. Thesis, University of Arizona.

Longcamp, M., Boucard, C., Gilhodes, J. C., & Anton, J. L. (2008). Learning through hand- or typewriting influences visual recognition of new graphic shapes: Behavioral and functional imaging evidence. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 20(5), 802-815.

Longcamp, M., Boucard, C., Gilhodes, J. C., & Velay, J. L. (2006). Remembering the orientation of newly learned characters depends on the associated writing knowledge: A comparison between handwriting and typing. Human Movement Science, 25(4-5), 646-656.

Smoker, T. J., Murphy, C. E., & Rockwell, A. K. (2009). Comparing memory for handwriting versus typing. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 53(22), 1744-1747.

Washburne, C., & Mabel, M. (1937). Manuscript writing – some recent investigations. The Elementary School Journal, 37, 517-529.

Wiley, R.W., & Rapp, B. (2021). The effects of handwriting experience of literacy learning. Psychological Science, 32(7), 1086–1103.

Re the research on cursive vs. printing: There's a New York Times article from 2014 (https://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/03/science/whats-lost-as-handwriting-fades.html?_r=) that says there's evidence that cursive and printing may activate two separate brain networks, suggesting that teaching both may activate more cognitive resources.

The article also says that Dr. Virginia Berninger has suggested "that cursive writing may train self-control ability in a way that other modes of writing do not, and some researchers argue that it may even be a path to treating dyslexia." The author cites a 2012 review (https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/35808) suggesting that cursive instruction may be particularly helpful for people with dysgraphia.

I wonder if you came across any of that research and/or whether you feel it's convincing?

THANK YOU for this!!

As an ESL teacher at the secondary level, I often wonder if the benefits of handwriting that we see in primary students could be extended to begjnner-level high school newcomer students, who are also acquiring vocabulary and learning spelling strategies, etc. Any thoughts?