Edu-Snippets

Social cues and the embodiment principle; the educational benefits of prequestioning.

Highlights:

Adding the social cue of pointing can further enhance the effectiveness of on-screen pedagogical agents (human-like characters) on learning.

Pretesting (also known as prequestioning) is a simple and effective way to improve student learning.

How can we design pedagogical agents (onscreen life-like characters) to maximize learning?

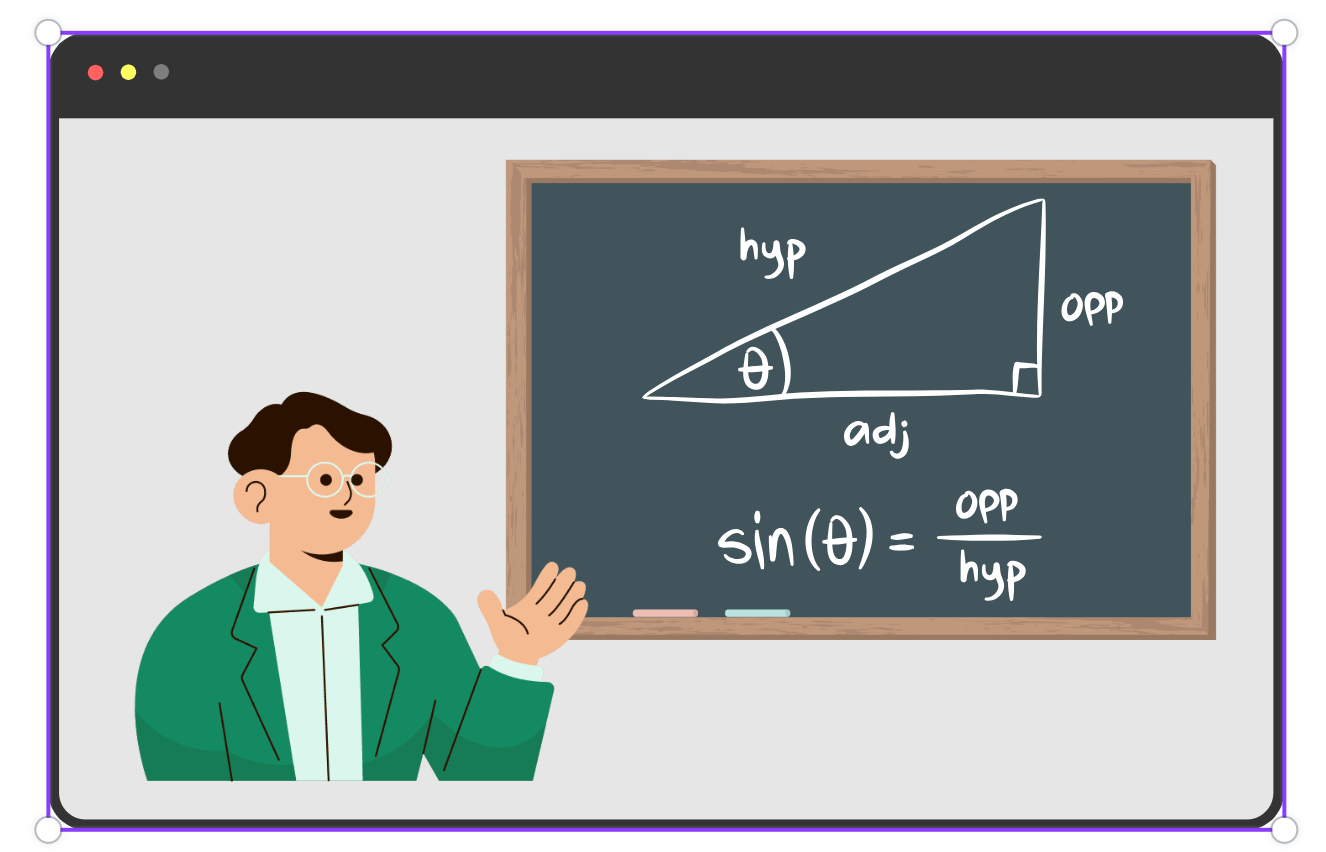

Instructional videos sometimes contain an animated cartoon character (like the one at the top of this page) that acts as an on-screen teacher. Educational researchers refer to these characters as “Pedagogical Agents” or PAs. Their purpose is to humanize instruction by providing learners with a friendly, life-like guide that talks to learners and explains concepts.

A recent study by Li, Wang, and Mayer (2023), entitled, “How to guide learners' processing of multimedia lessons with pedagogical agents” explored how to design pedagogical agents to best support learning. Should a pedagogical agent face the learner, making eye contact? Or should the direction of the agent’s gaze focus on relevant items of interest on the screen? Or should the agent gesture and point at objects? What works the best?

Li, Wang, and Mayer (2023)’s research builds on decades of experiments. Initially, researchers were unsure whether pedagogical agents were beneficial or not. One study found that pedagogical agents did not contribute to learning (Mayer et al., 2003; see also the seductive detail effect). However, other studies found that pedagogical agents had a small but significant effect on learning (Schroeder et al., 2013). These mixed results suggested that the effectiveness of pedagogical agents depended upon how pedagogical agents were implemented. Further research determined that pedagogical agents that used pointing, arm movements, eye movements, and gestures had a positive impact on learning, while static agents did not (Davis, 2018; Wang et al., 2022).

The latest study, by Li, Wang and Mayer (2023), was an effort to build on this body of research. What specific types of gestures and eye gaze work the best, and why? Should agents be designed to forge a social connection with the learner, using social cues like facial expressions and eye contact? Or is it better for the agent to exhibit attention-guiding cues, using gaze direction and pointing, to focus the learner’s attention on specific on-screen content?

The experiment:

To answer these questions, Li, Wang and Mayer (2023) ran experiments designed to disentangle the effects of social cues and attention-guiding cues adopted by onscreen agents on learning outcomes. The researchers created a set of four instructional videos that were virtually identical in all respects. However, in one video the agent gave lots of social cues but no attention-guiding cues. The pedagogical agent in another video gave attention-guiding cues but no social cues. The agent in a third video gave both types of cues. And the agent in a fourth video gave neither type. Then they recruited 128 university students to determine which video best promoted learning.

Results:

The experiment revealed that attention-guiding cues (pointing and looking at the relevant content) were more successful in helping learners fixate, remember, and understand the learning material compared to social cues (i.e., having the agent maintain eye contact with the learner). Social cues alone didn’t improve learning.

Take-away for learning designers:

It’s advisable to use pedagogical agents who use human-like expressions and gesturing while also integrating the attention-guiding social cues of pointing and looking at the relevant learning content. Social cues (facial expressions and making eye contact with the learner) do not benefit learning significantly. However, having the pedagogical agent looking directly at the learner can help humanize the instruction when the agent is talking about things that are not illustrated onscreen.

The Prequestion Effect: Does asking preliminary questions enhance learning?

Researchers have long known that prompting students to answer questions can be effective in promoting learning. The most well-known strategy of this sort is called “Retrieval Practice”. After being introduced to new material, engaging the learner in retrieval practice (e.g., by giving them a quiz) is an effective way of strengthening their memory of the new material. Dr. Pooja Agarwal, creator of retrievalpractice.org and co-author of Powerful Teaching, explains that when learners are prompted to recall something from long-term memory, they end up retaining that knowledge better and longer. Retrieval practice is a powerful technique for enhancing learning. Some of the more common forms of retrieval practice include flash cards, quizzes, brain dumps, and think-pair-share.

Retrieval practice is a question-asking strategy that teachers use after instruction has occurred. Recently, researchers have been wondering whether it might be beneficial to pose questions to learners before the instruction takes place. Will that also support learning? One obvious concern about posing questions before the instruction is that students won’t have any way of knowing the answers! Nevertheless, a growing body of research indicates that such testing – also known as prequestioning or pretesting or pretrieval practice — can benefit learning, as long as the correct answers are made available to the students afterwards (Carpenter et al., 2023; Pan & Carpenter, 2023).

In a recent study, Soderstrom and Bjork (2023) examined the impact of prequestioning on undergraduate students enrolled in a large research methods course. Before certain classes, students in the course were given a brief multiple-choice pretest on topics that would be covered in the subsequent lecture. In other classes, students were simply given a lecture without a pretest. On the final exam, at the end of the year, students had significantly better recall of the material that had been pretested, suggesting that the pretest step contributed to their learning.

Pan and Sana (2021) have also recently examined the impact of prequestioning. They ran an experiment with 1573 students that compared three conditions: 1) Pretest followed by lesson; 2) lesson followed by post-test (i.e., retrieval practice); and 3) lesson delivered without pretest or post-test (control group).

When tested two days later, students who were in the pretest or post-test condition had significantly better recall of the material than students in the control group. Pretesting and post-testing were found to be approximately equal in terms of their effectiveness.

An important question arises when we discuss pretesting: What makes it beneficial? Much is still unclear, but researchers believe that pretesting alerts learners to the kinds of information that they should watch for in the upcoming lesson (Yang et al, 2021).

Considerations while integrating prequestioning:

Carpenter et al. (2023) suggest that pretesting is best used with facts and concepts that are explicitly stated in a lesson, rather than information that must be inferred. Pretesting can be applied to a range of learning situations, including, videos, lectures, and assigned readings. It can take the form of multiple-choice questions, fill-in-the-blanks or short answer-type questions. According to Pan and Carpenter (2023), pretesting is a “flexible learning tool that can be adapted to a number of different lessons and contexts” (pg. 80). However, when designing a pretest, teachers need to remember that students will likely not know the answers to many, if not all, of the questions. This may be an unpleasant feeling for some students. Therefore, educators need to approach pretesting cautiously and provide students with appropriate warm-up and/or mental preparation prior to the pretest.

References

Carpenter, S. K., King-Shepard, Q., & Nokes-Malach, T. (2023). The prequestion effect: Why it is useful to ask students questions before they learn. In In their own words: What scholars want you to know about why and how to apply the science of learning in your academic setting (pp. 74–82). Division 2 American Psychological Association.

Davis, R. (2018). The impact of pedagogical agent gesturing in multimedia learning environments: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 24, 193-209.

Li, W., Wang, F. & Mayer, R. E. (2023). How to guide learners' processing of multimedia lessons with pedagogical agents. Learning and Instruction, 84.

Mayer, R. E., Dow, G. T., & Mayer, S. (2003). Multimedia Learning in an Interactive Self-Explaining Environment: What Works in the Design of Agent-Based Microworlds? Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(4), 806–812.

Pan, S., & Carpenter, S. (2023). Prequestioning and Pretesting Effects: a Review of Empirical Research, Theoretical Perspectives, and Implications for Educational Practice. Educational Psychology Review, 35, Article number: 97.

Pan, S. C., & Sana, F. (2021). Pretesting versus posttesting: Comparing the pedagogical benefits of errorful generation and retrieval practice. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 27(2), 237–257.

Schroeder, N., Adescope, O., & Gilbert, R. (2013). How Effective are Pedagogical Agents for Learning? A Meta-Analytic Review. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 49(1).

Soderstrom, N., & Bjork, E. (2023). Pretesting Enhances Learning in the Classroom. Educational Psychology Review, 35, Article number: 88.

Wang, F., Li, W., & Zhao, T. (2022). Multimedia learning with animated pedagogical agents. In R.E. Mayer & L. Fiorella, (Ed.), The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning (3rd ed., pp. 452–462). Cambridge University Press.

Yang, J., Zhang, Y., Pi, Z., & Xie, Y. (2021). Students' achievement motivation moderates the effects of interpolated pre-questions on attention and learning from video lectures. Learning and Individual Differences, 91, 102055.

I agree that "pretesting alerts learners to the kinds of information that they should watch for in the upcoming lesson" (Yang et al., 2021).

Based on pure intuition (not backed up by research), pretesting can help students focus on the most essential contents of the course during lectures. In situations where lecture contents are not "streamlined" (i.e., contain unnecessary details - and this is often the case), pretesting can have an even more substantial effect.

An interesting question is whether a fourth group with both pretest and post-test can significantly outperform any other group. I feel the combined technique would at least be as effective as either pretest or post-test alone.

Since I have a student with learning difficulties, I must design my teaching before any further research results emerge. I would combine pretests and post-tests this way:

1. Ask questions relating to the main structures of the course content in pretests, such as "What is a derivative" in a calculus course.

2. Cover the answers to the pretests in lectures.

3. Cover detailed explanations and scaffolded class exercises in lectures.

4. Ask exam-like questions in post-tests.

I hope this strategy, combined with spaced learning and interleaving, can help my student overcome his learning challenges.

I have successfully helped him once to improve his IELTS band score from 5.5 to 7.0 within 4 weeks, and I hope to successfully help him this time too!

While attention-guiding cues can lower the cognitive load by helping students focus on fewer contents, it is interesting that social cues alone cannot improve learning much. I initially thought that social cues provided by pedagogical agents might work since " teaching presence and social presence explain 69% of the variance in cognitive presence" in the Community of Inquiry model (Cleveland-Innes & Wilton, 2018, p. 14). However, according to the experiment in this study, they did not have such a strong effect on learning improvement.

I constantly feel that learning is a complex process involving cognitive processes, teaching and learning techniques, curriculum design and pedagogy, educational psychology, and much more. The settings in experiments can differ from online class situations. For example, participants in this study may perform differently since they knew they were participating in a one-time learning experiment without any consequences. In a real online class, they may have repeated involvement with the instructor and may have a high stake in their performance. As such, the motivation and behaviors can change, further affecting the course's efficacy.

I often feel that designing experiments to find answers in real-life situations is fun yet challenging. I will need further education to develop knowledge and skills to find answers.

Reference

Cleveland-Innes & Wilton (2018) Chapter 2: Theories Supporting Blended Learning, pages 9 -19 (no need to address the reflection questions in this resource), to learn about the CoI perspective as it relates to blended learning. Available at http://oasis.col.org/handle/11599/3095